In his prophetic essay The Abolition of Man (1944), C. S. Lewis asked whether the triumphs of modern science “may have been too rapid and purchased at too high a price.” While there is a place for modern biology and sciences, there is still room for the simple study of nature.

This is the very essence of natural history. Natural history is the branch of biological science that seeks to provide a descriptive account of plants and animals and the world in which they live. Although this branch of science been neglected in recent decades, it has traditionally been understood to be a necessary prerequisite to biology. Aristotle argued in his treatise On the Parts of Animals, that only “after considering the phenomena presented by animals, and their several parts,” can a student profitably “treat of the causes and the reason why.”

For this reason I am constantly surprised how many science curriculums want to skip ahead to more modern science topics such as cellular anatomy and physiology. Of course these are extremely useful science topics but I would argue leave them for a later time and while they are little, focus on what appeals naturally to children.

Children love plants and animals and bugs. Instead of spending a ton of time trying to make simple very difficult and detailed concepts, choose something that is effortlessly interesting. There is plenty of time to cover anatomy, cellular biology, and physiology, and in fact, the highschool textbooks will do so in great depth.

The way we learn best in any subject is to begin with things that are more familiar to us and afterwards to look into things that are hidden from view. To Aristotle, and to most generations of our ancestors, what was most familiar was precisely the created world: our own bodies, animals and plants, the features of the earth and sky (constellations), and the patterns of the weather.

This doesn’t come naturally for us anymore. We live apart from nature and consequently have little appreciation for the diversity and order of living things. The study of natural history helps us to deepen that appreciation, or, in the words of the philosopher Joseph Pieper, to “learn how to see again.”²

This is the season to revel in nature. Divulge in observation. Glory in being outdoors. Teach the children to pay attention. Teach them to observe details. Get each child a nature notebook where they can record their thoughts and make detailed drawings. A well done nature notebook is like a passport. Each drawing and description your stamp of record. Sure you could take a picture but a well done nature notebook is a thing of beauty, triumph, and achievement.

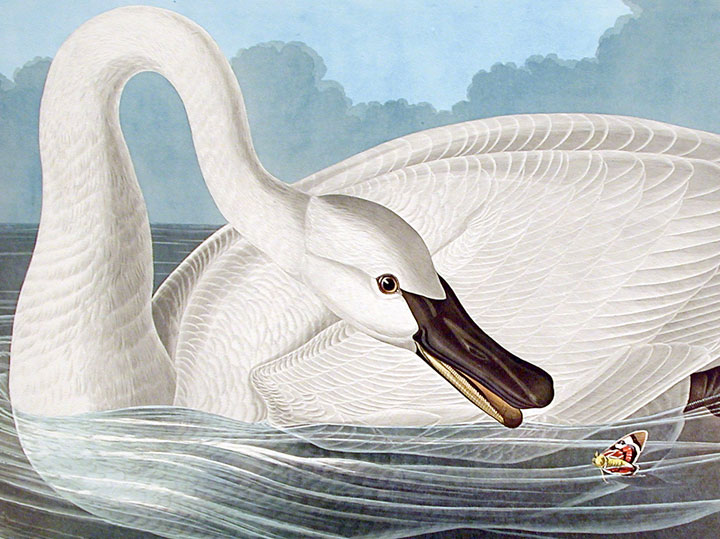

Spend a semester studying birds in depth. None of the high school sciences could ever afford that much time to revel in the beauty of birds. Learn and memorize the names of all the most common birds. Learn the birds that are native to you. By the time the child is in 6th grade they should be able to easily identify any bird they see flying around. I have never met a child who doesn’t like birds. Each time you can identify one it becomes a part of you–it is yours. Knowing 50 birds is like anywhere you go you see an old friend. “Oh look, it is a robin! Haven’t seen him here in a long time!” “The female cardinal is looking for her mate. There he is! He is such a beautiful red!”

Spend a year learning about bugs. There are millions of them and children are fascinated by them! Spend a day each week (or more) finding bugs, observing them, and recording them in a nature journal.

Spend a year learning about mammals and animals in general. Learn their bone structures. Learn about the uncommon ones. Science class will be a looked forward to with joy!

Curriculum recommendations:

Before biology students should be instilled with a love for the beauty and intelligibility of animals. In Nature’s Beautiful Order the study of animals is introduced through the eyes of the classical naturalists, scientists who always kept before them the fundamental truth that it is the whole animal, and not some tiny part of it like a cell, that is both best known to us and also the principal reason for our interest in the first place.

The writers whose works are presented in that book—chiefly John James Audubon, Jean-Henri Fabre, and St-George J. Mivart—were in this respect followers of Aristotle, the first and greatest of biologists.

Further Curriculum Recommended: